Ningbo History - Deliberate Release of Plague in Ningbo, Manchuria (1940)

- Details

- Category: Ningbo News

- Published: Tuesday, 14 May 2013 09:16

Perhaps the most astonishing thing I noted when interviewing family members of American survivors of the Ningpo plague epidemic in 1940 was the resilience they expressed. The can-do attitude reverberated from a horrific scene in then-Manchuria through the generations to a Starbucks cafe conversation over coffee.

We thank MD, HB, JW, GC, and the surviving American families who participated in our analysis of the 1940 plague attack in Ningbo, Manchuria. Our work is dedicated to all of the Chinese victims involved in the biological warfare attacks of World War II.

---------------

On October 27, 1940, members of Japanese Unit 731 conducted a live test deployment of plague-infected fleas in Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, a city south of Shanghai.

The 4th Division of Unit 731 (Production), with a staff of 50 to 70 personnel, was responsible for producing cholera, anthrax, typhoid, paratyphoid, and plague. The 4th Division achieved an operational output of 300 kilograms of plague per month.

These agents were tested against live prisoners at Anda Station, which was located in Anda City, Suihua, HeilongJiang, China (131 km northwest of Harbin and 2,638 km north of Ningbo), as shown in Figure 1.

f The location of Anda Station Proving Ground, 131 km northwest of Harbin and the location of Unit 731’s main production facility.

Anda Station was a proving ground to determine optimal weapon configurations, meteorological conditions, and other parameters related to successful field deployment. At Anda Station, live Chinese prisoners were subjected to experimental infection by plague-infected fleas.

One experiment involved tying 10 to 15 prisoners to stakes and dropping up to 10 porcelain bombs from airplanes containing plague-infected fleas. At peak operations during the war, Japanese officers testified that 600 prisoners died per year during tests.

The use of fleas as opposed to naked dispersal of live plague bacteria was developed by Ishii and announced to his staff as the preferred operational deployment method in June 1941 after live testing he supervised in Zhejiang Province in October 1940, which included the city of Ningbo. Of particular interest to the Japanese was the fact that the fleas survived the deployment by aircraft and survived long enough to sustain a chain of transmission on the ground. Japanese general military staff were not impressed with the overall size of the Ningbo epidemic, however they deemed the live test deployment to be a success, which prompted orders for a massive scale up of Unit 731 and 100 activities throughout China. This scale up included joint operations between Units 731 and 100 involving hundreds of personnel trapping rodents and breeding fleas for the purpose of plague weaponization in the latter half of the war.

Ishii and his team had discovered that naked agent dispersal of dysentery, cholera, paratyphoid, typhoid, cholera, and plague were inefficient due to low survival rates of the agents, particularly when deployed by aircraft at altitudes high enough to avoid ground artillery. Ishii believed air pressure and temperature at higher altitudes contributed to killing the pathogens. Naked agent was used in incendiary bombs that were completely destroyed in the heat of detonation. The use of arthropod carriers such as fleas enabled aircraft to avoid artillery, ensure longer agent survival times, and activate a chain of transmission that may involve enzootic cycles with indigenous hosts such as rodents, in the case of plague. The Japanese ultimately chose spraying apparatus on the wings of aircraft and porcelain bombs to convey plague-infected fleas to deployment zones.

Kawashima Kiyoshi, the commander of the 4th Division (Production) of Unit 731 from 1941 to 1943, testified to the Soviets in 1949,

... The apparatus for breeding fleas as carriers of epidemic diseases consisted of the following: in the detachment’s [Unit 731’s] 2nd Division [Testing] there were specially equipped premises capable of housing approximately 4,500 incubators. Three or four white mice were put through each incubator in the course of a month; these mice were held in the incubator by means of a special attachment device. There was a nutritive medium and several kinds of fleas in the incubator. The incubation period lasted three to four months, in the course of which each incubator yielded about ten grams of fleas. Thus, in three to four months the detachment bred about 45 kilograms of fleas suitable for infection with plague.

During the Khabarovsk Trial proceedings, Japanese military officers attached to Unit 731 testified plague-infected fleas were deployed by airplane over Ningbo in October 1940.

The Ningbo Plague Epidemic

The Japanese would later test their operational capabilities in Ningbo, Manchuria (near modern day Shanghai) in late 1940, triggering a plague epidemic. What follows are the accounts of two American families living local to the deployment area and local Chinese media.

Original hardcopies of Ningbo local media were unavailable. Copies of the original Chinese local media reports were available in the book, Chugokugawashiryo: Chugokushinryaku to nanasanichi butai no saikinsen [Chinese Side’s Material: Invasion to China and Unit 731’s Germ Warfare].

Archie Crouch, an American missionary living in China, was validated to have lived in Ningbo at the purported time of his experience based on references to him in Mabelle Smith’s diary. The Smith family were friends of the Crouchs, also deployed as missionaries in Ningbo. Crouch's manuscript, however, is a derivation of his original diary, of which an original copy was unavailable. It was unclear to what extent faithful reproduction of the information in his diary, by date, was represented.

Mabelle Smith’s personal diary was considered credible, albeit with brief entries owing to her use of a pre-printed template designed to enable the diarist to record a couple of lines a day across 5 years so that the same date’s entries across all 5 years could be visible on the same date page.

All three source-types generally agreed with each other in terms of factual information related to reports of a plague epidemic in downtown Ningbo that was significantly disruptive to daily life. There was some discrepancies about the specific date certain events occurred and when cases and fatalities were known. These discrepancies are noted in the below timeline.

The timeline represents a historical reconstruction of the plague epidemic based on available information and therefore should be considered an approximation of events.

Day -12: October 18th

Archie Crouch Manuscript

Radio media reported from Shanghai that the American government advised the immediate evacuation of all American citizens from Manchuria (China), Japan, French Indo-China (Vietnam), and the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). This announcement preceded Pearl Harbor by thirteen months. Crouch and his wife Ellen decided to stay so long as their Chinese colleagues did not feel endangered or embarrassed by their presence.

Day -5: October 25th

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“… cold. Put away summer things, clothes, etc. We pile on clothes and bedding to keep warm.”

Day -3: October 27th

Archie Crouch Manuscript

Crouch recorded a single-seater Japanese airplane flew into Ningbo just before twilight and slowly circled the center of the city before departing. He noted this was unusual given all prior Japanese air raids were daily from 1000 to 1500 involving multiple airplanes. As a point of context, Crouch indicated the daily routine was merchants would open shops at daybreak, close in the middle of the day, and reopen after 1700. The school where Crouch taught, Riverbend Christian Middle School, held classes inside from 0500 to 0900 as was the case for all other schools in Ningbo. From 0900 to 1700, classes were held outside under the cover of bamboo groves outside of campus. After 1700, classes resumed into the evening inside. Crouch indicated the population of Ningbo numbered more than 300,000.

Crouch noted the single-seater airplane released “a plume of what appeared to be dense smoke billowed out behind the fuselage… the cloud dispersed downward quickly like rain from a thunderhead.” The plane then departed the area. There was no record of public anxiety or concern about the event from other sources.

Day -2: October 28th

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“No fun to have Roy [her husband] gone when we expect the enemy!” Smith’s husband had left the prior day to visit a friend who had no money to evacuate to Shanghai.

Archie Crouch Manuscript

There was gossip in the city that the plane had dropped wheat, and people had collected it to feed to their chickens. When Crouch had arrived at school, teachers and students were speculating whether the event might be a kind of biological warfare.

Day 0: October 30th

According to local media, this was the first day fatalities due to plague was noted. There was no indication of awareness by either Smith or Crouch, and officials did not release information until three days later. It is unclear precisely when officials were aware of the fatalities.

Archie Crouch Manuscript

Crouch’s wife Ellen, pregnant with their second child, delivered at 0240. They named her Carolyn Elizabeth.

A telegram from the American Consulate in Shanghai had been received by Crouch and the missionary community, urging again to evacuate China immediately and that a ship was standing by in Shanghai. Crouch noted there were rumors of Japanese army advancing towards Ningbo from the south.

Day 2: November 1st

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“Tea at Billie’s where we Americans met and decided to telegraph Shanghai that none of us wanted to leave.” Smith’s diary entries until November 3rd were preoccupied with the birth of Carolyn Elizabeth Crouch.

Archie Crouch Manuscript

Twenty people had contracted suspected plague in the center of the city. Although laboratory evaluation was pending, physicians believed the clinical signs were consistent with plague. They notified city officials and requested cordoning off the affected areas with transportation restricted only to medical personnel. Crouch advised his colleagues not to ride in rickshas due to possible exposure to fleas and lice. They put rat poison in the school and their homes. Local merchants were already seeing high public demand for rat poison and traps. Crouch kept his young son restricted to their yard and concocted a mixture of soap and kerosene to scrub the inside of his house.

Day 3: November 2, 1940

Ningbo Local Media

Local media reported the first cases of “an acute epidemic disease”. More than 10 fatalities were reported over the prior three days, and symptoms were described as headache, high fever, chills, and unconsciousness and diarrhea in severe cases. The victims were found on Kaiming Street, Ludong Town and Donghou Street, Donghou Street in Tangta Town, which were areas within in the city of Ningbo. Ludong Town officials discovered a large number of people ill with similar symptoms and called for emergency transport of the affected by car to the Central Hospital. Officials were unsure of the diagnosis.

The situation was considered serious enough for the lead official responsible for Ludong Town to send a telegram to the Director of the Yin County Health Center asking for his immediate physical presence. The Director, after visiting the affected areas and hospitalized patients, sent a telegram to the county government requesting immediate personnel deployment to conduct an emergency disinfection campaign.

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“[Japanese] planes came several times but flew over.”

Archie Crouch Manuscript

Bubonic plague was now confirmed, and 16 additional fatalities were reported. Local Chinese media reported on the causes, symptoms, and treatments of plague.

Day 4: November 3rd

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“Bubonic plague has broken out in center of city! What next? Quarantine[d] district infected.”

Archie Crouch Manuscript

Schools without boarding facilities were ordered closed. Riverside, the school that Crouch taught at, took in as many boarding children as possible and then closed their gates. Cleaning crews were in the streets to collect garbage. Posters with illustrations of rodents and fleas appeared on walls throughout the city to encourage compliance with sanitation.

Day 5: November 4th

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“In [evening] went to Riverside to talk over plague situation and decided to close school for a week.”

Day 6: November 5th

Ningbo Local Media

Local media declares the presence of “catastrophic plague” in Ningbo and publishes an announcement by the County Magistrate, who had activated Order No. 291: strict quarantine for all affected areas. This edict included not only travel restrictions in the affected areas of Kaiming and Donghou Streets but encouragement to the entire county population to refuse refuge for fleeing residents. Residents were encouraged to police and report on those not adhering to the new regulations. The County Magistrate, emphasizing adherence to Order No. 291, declared the situation was “a matter of residents’ lives”.

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“Twenty people died yesterday of plague. It has spread out to West Gate. All schools ordered closed.”

Day 7: November 6th

Ningbo Local Media

The Yin County Magistrate was attending a meeting in Zhejiang Province when he received a telegram request to return immediately and lead the response campaign in Ningbo along with the senior provincial health technician, two additional senior technicians, and 30 quarantine personnel. Medical supplies were mobilized and expected to arrive the next day.

By this point, 20 suspect cases had been identified both within the affected areas and outside who had escaped the outbreak zone. Local officials had created an ad hoc screening and quarantine facility called “Yibu Isolation Hospital” at Yongyao Electric Power Company to screen, disinfect, and quarantine those individuals from the outbreak zone thought to have been exposed. All residents were routed through a disinfection area, forced to bathe and give up their clothes and bedrolls for incineration, and given new clothes and bedrolls before boarding within the hospital for the allotted quarantine period designed to rule out infection. It is unclear how long this period was except reference to an unspecified “incubation period”. “Bingbu Isolation Hospital” was for patients from Yibu who exhibited symptoms suspicious for plague but not yet confirmed through laboratory evaluation. Yibu was created inside Tongshun Grocery Store on Kaiming Street. “Jiabu Isolation Hospital”, a critical care unit to treat confirmed cases, was created on Touhou Street. Jiabu had admitted 6 new patients among 12 already in-house. Eleven other patients had already died. Nine patients were confirmed infected with plague in the prior evening. Patient flow proceeded from Yibu to Bingbu to Jiabu. To prevent patient escapes, Ningbo city police squads guarded all of these facilities.

A “quarantine office” was created in Minguang Theater, which served as the coordination center for cleaning crews, disinfection campaigns, and disease control activities. More than a dozen traditional Chinese medicine practitioners met in a private residence to offer their assistance to the quarantine office.

Schools were ordered closed and teachers were ordered to attend public awareness campaigns. One hotel was ordered closed due to suspicion of harboring escapees. Local media suggested broader hotel closure orders would be issued.

In addition to Ludong and Tangta Towns, Xiangdong Town reported suspect cases. Officials issued disinfection and cleaning orders. Jiangbei Town held disease prevention and control meetings as a preparatory measure.

Nine plague fatalities were buried in Laolong Bay. Clustering of deaths within the same household was noted.

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“Wednesday meeting well attended. I feared fleas would get on me, am always conscious of fleas these days. Made marshmallows and took to Ellen; also took a rose to her. Cooler weather. We close welfare school.”

Day 8: November 7th

Ningbo Local Media

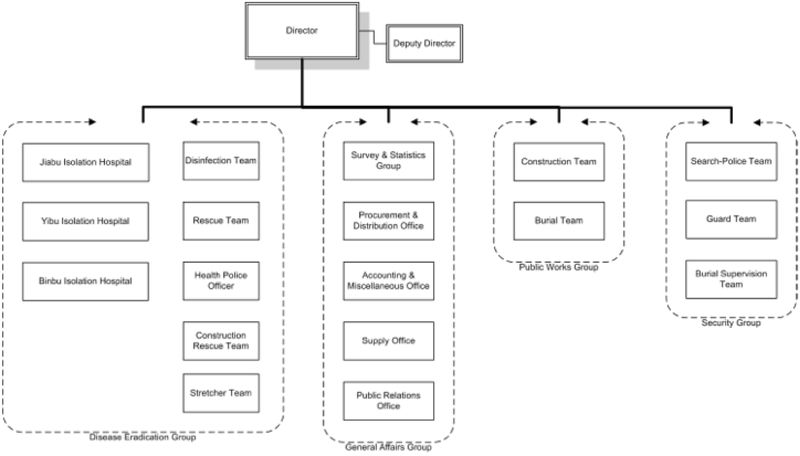

Yin County convened a large public health meeting to coordinate the response effort. The Epidemic Prevention Bureau was established with the Provincial Secretary as its director. A work plan was discussed to integrate provincial, county, and local town workers’ activities. Four divisions were created under the Yin County Epidemic Prevention Bureau:

Disease Eradication Group. This group managed the Yibu, Jiabu, and Bingbu Isolation Hospitals. The structure of each of these ad hoc hospitals was requested to include a treatment room that would accommodate both Western medicine-trained and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners and a disinfection room staffed by a single nurse in a protection suit. The hospitals would serve as bases for deploying disinfection, rescue, and emergency transport teams.General Affairs Group. This group included administrative and public relations function.Public Works Group. This group’s focus was construction and burial. The construction team would play a key role in building a containment wall around the outbreak zone in the coming days.Security Group. This group included mobile police units that captured citizen reports of additional cases and escapees.An elaborate and precise description of personnel in charge of these groups, the management hierarchy, and work schedule was presented. An aggressive public hiring program for nursing staff was initiated.

Traditional Chinese medicine practitioners presented an herbal remedy to the public and were rebuffed by local media and officials. The reason used was official concern that residents would attempt self-medication at home, delaying not only treatment but also isolation to prevent further epidemic spread. Officials requested that all physicians wishing to participate in response do so at the isolation hospitals as opposed to their private clinics.

The Yin County Lodging Union sent announcements to its members urging them to be vigilant for escapees and ill individuals to protect lives and commercial interests.

An additional five cases were identified in the outbreak zone and admitted to Jiabu Isolation Hospital, where eight fatalities were reported and buried in Laolong Bay. Laolong Bay had become the designated public burial site. An additional 35 patients were admitted to Yibu Isolation Hospital, which brought the total number of inpatients to 67. Seventy additional patients were admitted to Bingbu Isolation Hospital.

The cumulative death toll was 47.

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“Fewer deaths yesterday. Planning to burn houses in that district!”

Day 9: November 8th

Ningbo Local Media

As the operations of the newly formed Epidemic Prevention Bureau began, there was concern among the responders about potential exposure to plague. Several members of the disinfection and security teams asked for medical evaluations to rule out infection. As homes were quarantined, cement containment walls were built around the homes to prevent the escape of rodents.

Escapees continued to be identified, captured, and returned to the isolation hospitals.

Day 10: November 9th

Ningbo Local Media

The Central Epidemic Prevention Team from the provincial government was due to arrive the following day, and the Epidemic Prevention Bureau held a meeting to prepare for their arrival. A plague vaccination campaign with plague serum was started to cover the neighboring areas of the outbreak zone: Chiyou Street (eastern boundry), Daliang Street (southern boundry), Nanbei Avenue (western boundry), Canghsui Street (northern boundry). A private physician donor offered two dozen gas masks and 15 standard masks to the Epidemic Prevention Bureau.

Fourteen escapees who were suspect plague patients were captured and returned to the Yibu Isolation Hospital and their homes disinfected.

Traditional Chinese medical practitioners opened the Chinese Medical Center and treated three patients, transferring two to the Binbu and Yibu Isolation Hospitals, respectively. At Jiabu Isolation Hospital, 7 patients were admitted the prior day, bringing the total number of inpatients to 11, with 8 fatalities. The bodies were taken to Laolong Bay for burial. Two wild dogs found in the outbreak zone were shot, disinfected, and buried in Laolong Bay as well.

Day 11: November 10th

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“No [church] services in city because of plague… Archie [Crouch] here for supper, waffles.”

Day 12: November 11th

Ningbo Local Media

The Director of the Zhejiang Province Health Bureau arriving in Ningbo with 30,000 doses of plague serum. The Central Epidemic Prevention Team welcomed the new arrival of its coordination lead and nine additional staff members who were detailed from the provincial health bureau and stood up a base of operations at the Hanxiang Elementary School on Cangji Street. This group made a site visit to the Laolong Bay burial site.

Yin County provided phone numbers were provided to the community to report dead rodents, ill or dead individuals, discovery of escapees or goods being moved illegally from the outbreak zone, and areas requiring disinfection.

The culmulative death toll was 60. Accurate mortality counts varied by one to three from day to day, which was a reflection of challenges in coordinating reporting between three hospitals, senior official reporting, and the media. At this point, Yibu Isolation Hospital reported 3 new inpatients. Bingbu Isolation Hospital reported 13 total inpatients, and Jiabu Isolation Hospital reported 11 total inpatients and 4 fatalities. Three additional infected patients and seven deceased individuals were retrieved from the city. The anxious well presented themselves for testing.

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“Vacation in school today and tomorrow because of plague.”

Day 13: November 12th

Ningbo Local Media

The Yin County Epidemic Prevention Bureau, Central Epidemic Prevention Team, and Zhejiang Province Health Bureau held a coordination meeting and created several new teams: technical, inoculation, environmental health, quarantine, and a “Remedial Measures Committee”. A disinfection building was constructed for the Public Works Group to disinfect clothes and goods from the outbreak zone. Concern was expressed about the possible leakage of infected bodily fluids from the Laolong Bay burial site and proximity to the river. The group decided to move the burial site to an area distant from water sources with a cement containment wall constructed to prevent fluids from leaking into the ground. Protection suits were issued to healthcare providers, disinfection, and burial team members. The complexity of the entire response operation placed an economic strain on the community, and questions were raised about pay and reimbursement.

The Director of the Zhejiang Provincial Health Bureau reviewed the history of plague in China with the group, stating the first appearance was as an outbreak in 1911 in Shandong Province and later in Fujian Province. Without providing a specific date (later clarified on Day 17 as having occurred in 1939), the Director mentioned an outbreak of plague that had occurred in Qingyuan, approximately 500 km to the southwest of Ningbo, which was thought to have been an extension of disease activity in Fujian Province.

Enough plague serum was procured by the Provincial Health Bureau to inoculate 100,000 people. Rodenticides and traps were also procured. School closures were reiterated, with initiation of a plan to vaccinate the children and staff. Once the vaccination campaign was completed, schools would resume.

Jiabu Isolation Hospital reported 10 inpatients and 8 fatalities. Four new inpatients were reported at Yibu Isolation Hospital, which brought the total number of inpatients to 140. One patient fled Bingbu Isolation Hospital, which reported 7 total inpatients. Treatment teams ranging into the outbreak zone found an additional 5 suspect cases and one fatality.

A new outbreak area was discovered at Yongming Temple, Cixi County, which was 63 km north-north east of the original outbreak zone. A man, his brother, father, and mother were infected. The man died, as did his mother. His father was already hospitalized at Jiabu Isolation Hospital. This prompted designation of Yongming Temple as an outbreak zone that required transportation restrictions. Members of the Provincial Health Bureau were dispatched to the site.

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“No Wednesay meeting since plague still takes its toll… Heard over radio that of 2,300 [American] missionaries, only 200 are willing to go home.”

Day 15: November 14th

Ningbo Local Media

The media now described plague to be “epidemic” in Ningbo. Transportation routes from downtown Ningbo and Fenghua, 30 km south-south west, were ordered closed.

Additional financial resources by the Epidemic Prevention Bureau to the amount of 500,000 yuan were procured to manage recovery costs. This equates to 126 million in adjusted US dollars. The Bureau decided to incinerate those homes that could not be disinfected and reimburse the surviving inhabitants. Temporary homes were to be built within the month for the refugees. Concern about merchants withholding their inventory from disinfection teams was discussed at length.

In Jiagnbei Town across the river, sanitary inspection agents and additional road cleaners and garbage trucks were added to the response effort. The entire community was mobilized as part of a mass cleaning campaign and prevention measure. Cases were not reported from this area.

Jiabu hospital reported 8 inpatients and two new fatalities. Yibu reported 9 new admissions in addition to 153 inpatients, bringing the total to 162. Bingbu reported 9 total inpatients. Yibu and Bingbu Isolation Hospitals reported two new fatalities, which brought the total number of fatalities between the two facilities to 10. Planning to build new isolation wards for Jiabu and Bingbu hospitals was discussed.

Search teams found 10 escapees and returned them to the outbreak zone.

Day 17: November 16th

Ningbo Local Media

The vaccination teams were now inoculating 5,000 people daily. Suspect patients who had passed the incubation period symptom-free of plague were released from Yibu Isolation Hospital. Officials declared the situation had “passed the critical point”, where it was believed disease activity was waning.

The total number of patients at Jiabu, Yibu and Bingbu hospitals was now 183. One fatal case was reported the prior day. Jiabu had admitted six patients the prior day. Yibu, with 162 patients under treatment, admitted eight new patients. Yibu could not receive more patients and would transfer any new admissions to Jiabu and Bingbu. Bingbu reported 7 inpatients.

Two escapees were found and returned to the outbreak zone.

The public was now complaining that official countermeasures were excessive and unnecessary now that the peak of disease activity had passed. Some citizens even expressed doubt an outbreak had even occurred. Officials, who encouraged the public to remain focused and vigilant, denounced these claims.

Results of a summary epidemiological investigation conducted from October 30 to November 10 were presented that revealed the main outbreak zone was from 248 Zhongshandong Road via Kaiming Street through 142 Donghou Street. It was realized that there were no survivors when residents from adjacent homes were infected. Traditional Chinese remedies were found to be ineffective. The officials expressed surprise with how virulent the disease was and how high the mortality rate was.

Officials emphasized to the public the difficulty in achieving eradication, reminding them of Hong Kong, were it took 21 years to renovate all of the city buildings to inhibit rodent entry. The recent history of plague activity in China was reviewed, citing the plague outbreak in Longyan County, Fujian Province, had occurred in 1928. The plague outbreak in Qingyuan County, Zhejiang Province (500 km from Ningbo) had occurred in 1939. Officials pledged to build a permanent isolation hospital at Dongxiaoji Mausolem and closed their announcement by emphasizing unity in achieving the end goal of eradication.

Day 19: November 18th

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“No school until Thursday because of the plague, so far plague mortality 100%.”

Day 20: November 19th

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“No planes for three days.”

Day 21: November 20th

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“Planes fly over today.”

Day 22: November 21st

Ningbo Local Media

An outbreak of malaria was discovered, where two suspect plague patients at Jiabu hospital were found to have malaria and died.

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“We decide to give money to burned out plague families.”

Day 25: November 24th

Ningbo Local Media

All goods and household items within the outbreak zone were mobilized for disinfection, and a new Disinfection Office was created to manage this process. Household quarantine measures were about to be lifted. One suspect plague patient died in his home.

Day 26: November 25th

Ningbo Local Media

Household quarantine was lifted, and people returned to their homes to collect their belongings and clean their home. Once the home cleaning is approved by officials, a rehabitation certification would be issued.

Notification was received by the Epidemic Prevention Bureau there was an outbreak of plague in Quxian, Sichuan Province, nearly 2,000 km west of Ningbo.

Day 27: November 26th

Ningbo Local Media

Disinfection activities were reported to include metal bed frames, mahogany furniture, fixtures, doors, window glass, and lighting equipment. This process was expected to take another four days.

All dogs and cats in the outbreak zone were rounded up and killed. A massive incineration campaign was planned to begin on the evening of December 30th and targeted the destruction of 11 sites along Kaiming Street and Kaiming Alley. More than eleven fire brigades were called on to initiate a controlled burn, and armed police and guards were mobilized to protect the incineration sites from entry.

Day 28: November 27th

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“Women find it hard to come to Wednesday meeting as they must go for their 1/3 sharing of rice and stand in line all hours… Sirens every day but few planes.”

Day 30: November 29th

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“Plague stopped, 85 deaths.”

Day 31: November 30th

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“Bubonic plague area burned in city this evening… huge fire.”

Day 32: December 1st

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“Roy and I go to hospital to turn over [money] to Dr. Ting for people burned out in plague area in Ningbo.”

Archie Crouch Manuscript

Crouch notes the burning of the city occurred at 1900 the night of December 1, in conflict with Smith’s account.

Day 34: December 3rd

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“Heard at noon that [an orderly] at [the] hospital had died of pneumonic plague! Very serious. We postpone Missionary Association [meeting] which should have been at nurse’s home this evening.”

Archie Crouch Manuscript

Crouch noted the death of the orderly due to pneumonic plague, with the word pneumonic underlined in his manuscript. Crouch indicated local Chinese newspapers claimed a Japanese airplane intentionally released plague, which caused the epidemic.

Day 35: December 4th

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“A man spoke on the plague and showed plague pictures.”

Day 37: December 6th

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“Letters from Shanghai tell of many evacuating of our mission and urging Crouches to plan to go. Such news gets us all upset.”

Day 38: December 7th

Mabelle Smith’s Diary

“Sirens and planes busy, have been bombing several place near here of late. School children run to bomb shelter again.”

---------------

Members of Japanese Unit 731 were familiar with optimal methods and meteorological conditions to deploy plague. There was change in the season, with the onset of a cold front on Day -5, two days prior to the appearance of the single airplane dropping flea-infested wheat in Ningbo.

Contemporary reviews of the Ningbo plague epidemic suggested Japanese intelligence officers documented the results of the deployment closely through the monitoring of local Chinese media and periodic fly-bys. One such aerial reconnaissance was documented on Day 3.

Some have suggested local Chinese media blamed the Japanese for the plague epidemic. There was no indication of local awareness of an intentional release of plague other than documentation of local rumor on Day -2 in Crouch's diary and claims that Chinese media reported the epidemic was a biological attack by the Japanese on Day 34.

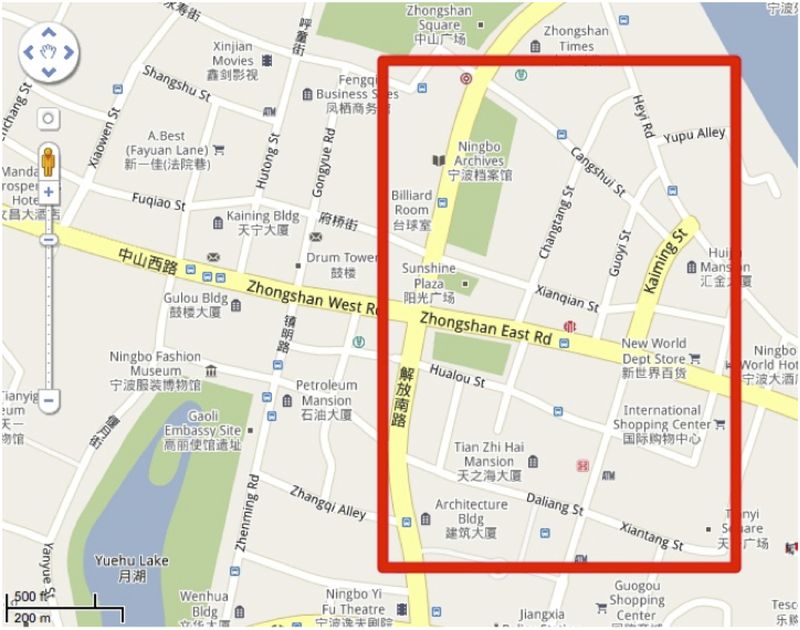

Figure 2 displays a modern city street map of Ningbo. The circled areas represent sites of reported cases. These sites are approximate, as only some of the streets have retained the same names since World War II such as Canghsui Street, Kaiming Street, Daliang Street, and Zhongshandong Road

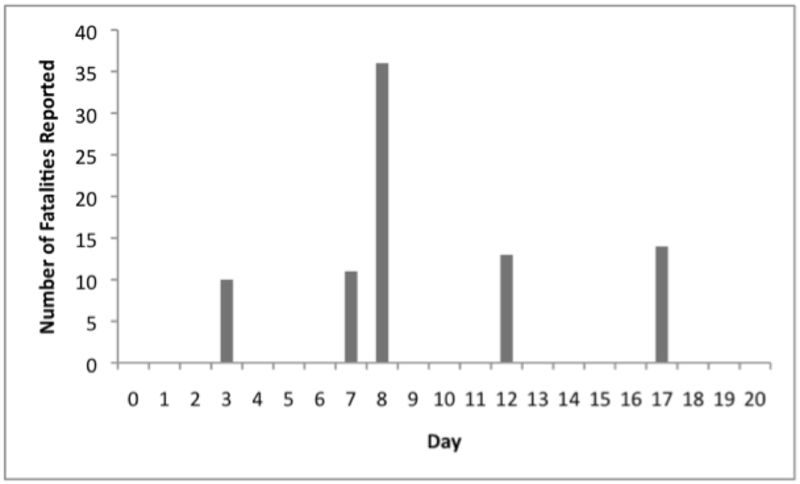

Figure 2. Map of Ningbo in relation to Shanghai [a], the downtown area that was the outbreak zone [b], and Cixi County, the site of outbreak extension reported on November 12th (Day 13). Maps produced using Google Maps.Figure 3 displays the reported daily fatalities. Daily reporting of epidemiological statistics were difficult to interpret due to discrepancies between the text and tables as well as differences between daily versus cumulative fatalities printed in local Ningbo newspapers. Figure 3 represents an extrapolation based on cumulative fatalities reported on five separate days. Fatalities reported on Day 3 represented cumulative fatalities over the prior three days. On approximately Day 8, the peak of fatalities was documented. We hypothesize the absolute number of fatalities represented by this peak may have been lower in the actual epidemic curve, as it reflects subsequent effort to range into the outbreak zone on foot and identify dying and already-dead individuals in their homes that may have died prior to Day 8. Officials declared plague to be “epidemic” on Day 15 and then “passed the critical point” on Day 17.

Figure 3. Daily fatalities reported by local media in Ningbo. Fatalities reported on Day 3 were cumulative from the prior 3 days.

Table 2 below represents a direct translation from a local Ningbo newspaper, Shishi Gongbao, reporting summary findings of the Epidemic Prevention Bureau as of November 16, 1940 (Day 15). More fatalities were reported with mortality close to 100%, as indicated by Mabelle Smith’s diary accounts on November 18th, noting 100% mortality, and November 29th, noting 85 fatalities, followed by report of pneumonic plague by Americans on the ground on December 3rd. Other accounts suggest the total number of infected was 100, and the mortality was 100%. One case of pneumonic plague was reported, which was 1% of the total cases, if the true number of infected was 100. Bubonic, primary sepsis, and meningitic cases were not differentiated in the reporting. For comparison, the United States reports 1 to 40 cases of plague annually over a far larger geographic area, the American Southwest. The majority of cases are bubonic (85%), followed by 13% with primary sepsis. As many as 6% of cases presenting as primary sepsis may progress to meningitis. Pneumonic cases account for 1-2% of all cases reported annually in the United States, similar to the percentages reported in Ningbo. If one considers 100 cases and fatalities to be the true number infected out of 173 residents listed in Table 2, then the attack rate was as high as 58% in the affected neighborhood.

Table 2. Summary of epidemiological findings by the Yin County Epidemic Prevention Bureau as of Day 15 of the epidemic. The entry line corresponding to 82 Kaiming was incomplete and not included in the totals. Dates of exposure, infection, or fatality were not reported.

What is apparent from media reporting and Crouch’s account was that cases were clustered spatially. Also remarkable was the notation that 7 entire families were killed. It is likely some, if not all of the other 3 families referred to in Table 2 as “infected” died in their entirety as well given antibiotics were unavailable at the time. It is unclear if any additional families were killed before the end of the epidemic.

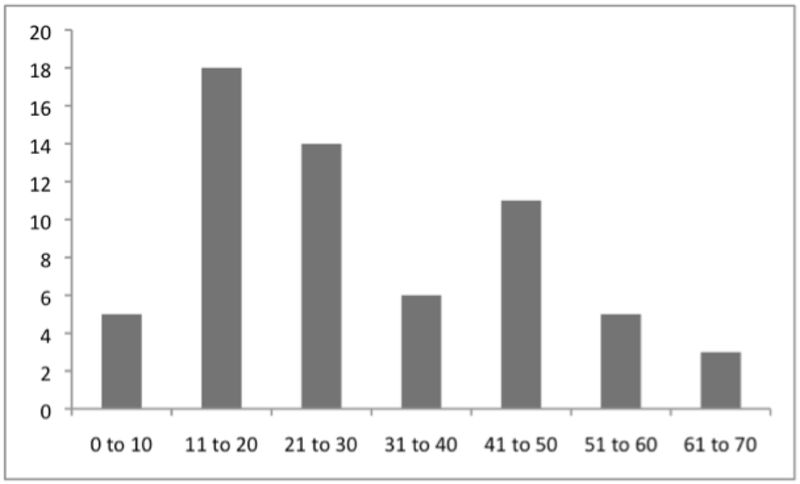

Figure 4 displays the ages of fatal cases, which was a sampling of 62 fatalities reported by officials via local media. Reported fatal case ages ranged from 5 years to 67 years old, with the bulk of fatalities (29%) in the 11 to 20 year old age bracket. More information was available for gender distribution of fatal cases: the distribution by gender for fatalities was 42 (63%) male and 25 (37%) female cases, accounting for 67 fatalities.

Figure 4. Age ranges of fatal plague cases in Ningbo.

The incubation period of plague is 2 to 8 days. No preceding rodent die-off was reported. The majority (approximately 68%) of fatalities were reported prior to or on Day 8. This supports a hypothesis that primary exposure occurred through physical contact with flea-infested wheat deployed by the Japanese into the streets. Although no concurrent rodent die-off was reported, it is likely initial fatalities seen up to Day 8 were through the direct exposure of flea-contaminated wheat gathered by hand from the streets, followed later by indigenous rodent exposure, triggering of an epizootic, and subsequent human exposures as local flea populations became infected. This secondary mechanism of transmission was brought to a halt through aggressive control measures by Chinese authorities, to include the physical destruction of the epicenter by fire.

---------------

When considering the Ningbo plague epidemic, it becomes important to understand the temporal, cultural, epidemiological, medical, and sociological baseline and context. Specifically:

What was the availability of pre-event warning, situational awareness, or other rumor network-mediated awareness of threat levels related to Japanese use of biological weapons in Zhejiang Province at the time?What were the typical, routine infectious diseases observed in the Ningbo of the 1930s and 1940s? How quickly did Ningbo physicians suspect plague as the cause of the epidemic?What was the indigenous baseline standard of medical care and public health in Ningbo at the time? What was the Chinese public’s expectation for access to medical care? What is the potential for public outcry or civil unrest if the public’s expectation for a given standard of care is violated?These questions address the level of preparedness in terms of warning systems and available local countermeasures, ability to discern routine versus non-routine infectious disease events, and effective response within the context of public cooperation.

On Day -2 following the appearance of the single Japanese airplane that dropped plague-infested wheat in Ningbo, Crouch indicated there was speculation and rumor whether the material was some form of biological warfare. It is important to recall Crouch’s manuscript is a derivation of his original diary, of which Praecipio International researchers did not find a copy. Therefore, the credibility of this statement is in question. It is unclear what a priori local knowledge or rumor those comments would have been inspired by among teachers and students at a local elementary school. The two prior field tests or theater deployments of biological weaponry by the Japanese occurred prior to the Ningbo plague epidemic. One was against the Soviets and Mongolians in the summer of 1939 on Khalkha River near the eastern border of modern-day Mongolia, 2800 km north of Ningbo. Given these military actions did not involve the Chinese army, it is unlikely this incident would have been present in Ningbo’s local rumor. Another event was the intentional deployment of plague-infected fleas in Quzhou, Zhejiang Province, on October 4, 1940 that killed nearly 275 people. Quzhou is approximately 325 km southwest-west of Ningbo. It is possible rumor of this event reached local Ningbo officials and most certainly reached provincial officials prior to their involvement in the Ningbo response. It is curious, however, the Quzhou epidemic was not mentioned by provincial officials in their media statements on Days 13 and 17. They instead discussed the epidemic of Qingyuan, approximately 500 km to the southwest of Ningbo. There was no claim of intentional deployment by the Japanese in Quingyuan, and available evidence does not indicate this was a site of Japanese BW deployments.

The threat of the encroaching Japanese was evident in the Crouch manuscript and Smith’s diary. Urgent notices to evacuate from the United States consulate, along with daily bombing runs of Ningbo by the Japanese accented the level of personal risk to the ex-pats and Chinese citizens resident in the city. It is possible this context of threat contributed to local blame being placed on the Japanese. The phenomenon of “scape-goating” in infectious disease crises is a common behavior to explain the non-routine.

According to Crouch, clinical suspicion for plague was nearly immediate, which is remarkable given there was no prior local experience with plague. The 1939 plague outbreak in Qingyuan County, Zhejiang Province was 500 km from Ningbo. The Quzhou plague epidemic triggered by the Japanese in the same month was 325 km away from Ningbo. It remains unclear how local physicians, many of whom were Western-trained, came to suspect plague. It is possible one of the local physicians was present at that outbreak or heard of it through media reporting or word of mouth. It may also be hypothesized the physicians were familiar with plague from textbooks or prior training. Crouch indicated he was provided a medical manual prior to his stay in Manchuria that discussed the symptoms, signs, and treatment of plague.

Discrepancies were noted in local knowledge about plague transmission, which was elucidated by Yersin in 1894 and Simond in 1898. On Day 27, locals attempted to disinfect window glass and doors prior to removal in preparation for the incineration of the outbreak zone on Day 30. This would appear to be an impractical measure if local authorities fully understood the microbiology and transmission of plague. There was no evidence of a rodent die-off that preceded human fatalities, a warning indicator that is well recognized in communities that have experience with endemic plague. Crouch asserts there was no plague in Ningbo prior to the epidemic. Lack of familiarity with disease epidemiology and the warning indicators of epidemic risk imply the community had limited to no prior experience with plague.

There was some delay in reporting of the event, presumably due to hierarchical community communication of fatalities to neighborhood authorities (Day 0 to 3), followed by transmission of the information to Yin County (Day 2 or 3) and then Zhejiang Province authorities (Day 7 or 8). This process of hierarchical communication of emergency information to the public likely contributed to time delays in warning from Day 0 to 3 and delays in broader engagement of response assets at the provincial level.

Medical countermeasures were not immediately available to Ningbo’s physicians, as evidenced by the external mobilization of plague antiserum by city and provincial officials beginning on Day 7. Plague antiserum was in use in Asia as far back as the 1890s, the product of Yersin and Simond’s work in South Asia. It is unclear what effect, if any, plague antiserum had on the treatment and prophylaxis of patients during the epidemic. This epidemic occurred at a time that preceded the discovery of streptomycin (1943), tetracycline (1962), and gentamicin (1963). Therefore, antibiotics were not available to the people of Ningbo, an important implication when considering plague approaches a near-100% mortality rate if untreated. Lack of local supply of plague anti-serum may be considered another indicator of little to no community familiarity with epidemic plague.

The elaborate organization of the Yin County Epidemic Prevention Bureau emerged on Day 8 (Figure 6), highlighting perception by officials that immediate and comprehensive response with full community participation was required. Emergence of novel decision-making and execution organizations is a classic indicator of a crisis. The total estimated direct cost of response in 2009-adjusted US dollars was 126 million.

Figure 6. The Yin County Epidemic Prevention Bureau.

Although antibiotics were unavailable to the people of Ningbo, non-pharmacological countermeasures were available. Officials engaged the entire community in response that sought to erect 14 foot high concrete barriers around individual homes and the entire affected neighborhood, disinfect goods and clean refuse from the streets, destroy rodents and companion animals, and rapidly identify and isolate suspect human cases. This is an important finding, as it highlighted the amount of collaboration and buy-in the officials and responders had with the public throughout much of the epidemic.

Anxiety was noted among officials and healthcare providers on Day 3 with the emergency public announcement of the epidemic. Public anxiety with extreme self-protection behaviors was noted quickly thereafter; by Day 7 escaping outbreak zone inhabitants were identified and returned to the isolation hospitals, which continued at least until Day 17. Patients fled not only the outbreak zone but also the hospitals themselves, hence the need for police and guards at all of the medical facilities. On Day 9, responders became publicly concerned about possible exposures to themselves. Attempts to evacuate are indicative of community disintegration (discussed below), a process driven by reports of unusual disease quickly killing entire families within a small community.

The general public did not show signs of outcry or dissent until Day 17, which was in the form of peaceful complaint related to a desire to return to normal activities of daily living and cessation of quarantine. Surprisingly, the media registered public claims that officials had fabricated the event, and no epidemic had actually occurred. Officials denounced these accusations and chastised the dissenters. There was no evidence of martial law being called into play in response to perceived erosion of official-public trust. It may be hypothesized the majority of the public understood the nature of the threat and was heavily invested in response, an indication of support for officials’ proposed actions during the crisis. It is also likely that effective risk communication by officials and immediate collaborative engagement of the public and the media mitigated the potential for social outcry.

Despite the tremendous damage inflicted on the affected neighborhoods in Ningbo, the Chinese residents and ex-pats supporting them displayed exceptional resilience in the face of the epidemic. This is remarkable when considering the locals came to understand the event was unusual, initially uncontrolled, killed children and entire families, and was understood to have been intentionally caused by the Japanese. It may be hypothesized the community had developed coping mechanisms to high threat, as evidenced by the routine migrations to rural settings in the middle of the day to avoid bombings. Self-protection behaviors were noted, however there was no evidence of a degradation of social ties to the point of true panic or selfish, animalistic behavior. These observations agree with disaster sociology literature suggesting true panic during disasters is rare to non-existent, where people have a tendency to form closer social bonds and social units as the community rallies in response.

Summary

Available evidence pertaining to the Ningbo plague epidemic suggests:

Local rumor of intentional BW use by the Japanese was present, however evidence was weak in the days preceding the epidemic due to possible recall bias in Crouch’s documentation. Subsequent evidence of Chinese suspicion of Japanese attack became stronger in the recovery phase of the epidemic, however original source material was unavailable for analysis but referred to by multiple secondary sources. Plague outbreaks or epidemics in Ningbo was not a routine, endemic phenomenon prior to the epidemic in question.Western-trained Chinese physicians were able to quickly suspect plague through clinical suspicion and later, laboratory diagnosis (microscopy).Standard baseline treatment for plague was plague anti-serum, the efficacy of which was grossly limited. Antibiotics and vaccine were unavailable. Response was predominantly non-pharmacological.Because there was no available and effective medical treatment for plague, there was no social expectation for a commensurate standard of medical care.There was little social outcry due to effective risk communication by officials and no social expectation for curative care. It may be argued this became a point of resilience for the community.Regionally, there was evidence of adaptive fitness emerging in the form of learned coordinated response, as members of the Yin Country Epidemic Prevention Bureau were requested in Quxian, Sichuan Province, nearly 2,000 km west of Ningbo. This request was based on the perception of their successful response efforts in Ningbo. Evolving adaptive fitness and response mobilization may be considered an indicator of geographic expansion of new knowledge as a result of experience. Framing the Epidemic as a Crisis or Disaster

When framing the question of whether the plague epidemic in Ningbo represented a simple event, crisis, or disaster, a heuristic model becomes useful to illustrate different types of infectious disease events. In this consideration, how an event became manifest becomes less important than assessing actual risk and impact in a live, rapidly evolving situation.

It is important to note the driver of a "crisis" being described as such, especially by the media, strongly relates to uncertainty. The Infectious Disease Impact Scale (IDIS) developed by Praecipio International in 2010 is a heuristic framework useful to explore the transition points between a routine, expected infectious disease event, unexpected crisis, and unmitigated disaster. This is a model in use operationally today for detection, assessment, and warning of significant infectious disease events.

Category 0: The unreported infectious disease event.

Daily, routine infectious diseases are handled at the IDIS category 0 level, and provision of warning about these diseases is not deemed 'relevant'. Non-routine infectious disease may also manifest as an unreported infectious disease event, implying the "astute clinician" in the local community network has not raised the concern something unusual was observed in the clinic, and nothing unusual was noted in local public health information feeds. This is the bleeding edge limitation of disease surveillance, where the first case of unusual infectious disease is often missed. Typical contemporary examples include a case of influenza-like illness, non-specific rash, or uncomplicated febrile illness seen by a healthcare provider.

The Ningbo plague epidemic remained at an IDIS Category 0 event from Days 0 through 3, likely due to time delays associated with physician recognition and reporting of unusual disease and local official investigation of the reports.

Category 1: The reported infectious disease event.

The typical IDIS Category 1 infectious disease event reported by a community reflects a sensitivity to public health or medical significance. Occasionally reporting reflects a sensational aspect of the disease in question such as contemporary reports of "flesh-eating" Streptococcal infection. Such language typically appears in media reports. No other significant features indicative of immediate public health or medical infrastructure impact, public anxiety, or civil unrest triggered by the event are noted. Other contemporary examples include report of a chickenpox outbreak, limited norovirus outbreak, or a single case of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

This transition point from IDIS category 0 to IDIS category 1 was not observed in the case of Ningbo, as the initial reporting of the epidemic became a public communication of emergency information, a jump to IDIS Category 3 discussed below.

Category 2: The infectious disease event associated with routine organized response.

IDIS category 2 events often reflect locally well-known diseases that nevertheless generate a demand for organization-level time-sensitive action. This action occurs locally and is routine. IDIS Category 2 events are the typical maximum level seen today in the United States. Current examples include routine community action for seasonal diarrheal disease in undeveloped countries or seasonal influenza in developed countries. It is important to note non-routine infectious disease may present as a Category 2 event, particularly when it shares similar clinical features with routine disease. The classic example is the appearance of pandemic influenza in the context of normal seasonal influenza, as was observed in April 2009 with pandemic H1N1, where similarity in clinical presentation masked the evolution of a crisis. Early indicators of pandemic H1N1 were difficult to distinguish from seasonal influenza because the level of impact had not reached "critical mass" to allow social recognition of the event as a threat. Indeed, it is highly likely pandemic H1N1 was transmitting in Mexico well before April 2009, undetected. Thus, the non-routine may present as routine.

The Ningbo plague epidemic was not reported as an IDIS Category 2 event; rather it jumped to an IDIS category 3 event when officials recognized a grossly unusual, non-routine event demanding immediate, organized response by authorities.

Category 3: Infectious disease event associated with non-routine organized response.

IDIS Category 3 events are essentially the beginnings of a community crisis. The operational definition of a crisis we are working from is the following:

An infectious disease event becomes a crisis when there is a recognized requirement for time-sensitive, non-routine organization-level decisions that may affect a local community’s activities of daily living. It is more common such decision-making falls within the organizational roles and responsibility of a public health institution than a public or private hospital or individual healthcare provider. This becomes a community level decision-making activity in countries where there is no public health capacity.

It is important to note Category 3 events may be associated with organized response features without significant broader social disruption, as evidenced in a Category 4 event. Current examples of an IDIS Category 3 event of event include a new vaccine-drifted influenza type A variant that appeared before an updated vaccine could be made available to the public. Another example is the 1999 introduction of West Nile virus to the United States, after recognition of the event to represent a public health threat. In this category it becomes important to understand the differences between organized response executed by public health authorities versus medical care such as that provided by a hospital. Consideration of both is crucial.

On Day 3, the plague epidemic in Ningbo moved from an IDIS Category 0 event to a Category 3 due to the quick recognition of grossly unusual geo-temporally clustered fatalities. Indications of crisis communication embodied by public emergency announcements, mobilization of local authorities, and requests for external assistance, were evidence of exceptions in official routine behavior.

Category 4: infectious disease event associated with social disruption

IDIS Category 4 events occur when organized response has been implemented, yet significant social disruption has been documented. The operational definition of social disruption considered here is:

Social disruption [of community vital processes] refers to the process where a community moves from a given level of integration towards disintegration.

Coleman’s (1966) original theory of community integration proposed “vital processes” of a community that “keep it alive as a community and prevent its disorganization”. These processes included:

Work;Education of children;Religiously related activities;Organized leisure activities;Unorganized social play of children and adults;Voluntary activities for charitable or other purposes;Treatment of sickness, birth, death (healthcare);Buying and selling of property;Buying consumable goods (food, etc.);Saving and borrowing money;Maintenance of physical facilities (roads, sewers, water, light);Protection from fire; andProtection from criminal acts.It is well recognized that infectious disease events may impact a community to the point of straining various aspects of these vital processes. Category 4 events may be associated with significant strain of multiple community vital processes without inducing community disintegration, which is the indication of a Category 5 event. Examples of Category 4 events include the 1957, 1968, and 2009 influenza pandemics and the introduction of Chikungunya to India in 2006.

On Day 6, a combination of local media declaring “catastrophic plague” and official concern for potential public-initiated evacuation and an order to quarantine the affected neighborhoods highlighted severe disruption of normal community activities of daily living in the outbreak zone.

Category 5. Infectious disease event associated with disaster indicators

We have not observed an IDIS category 5 event in the United States in contemporary society. The operational definition of a disaster considered here is:

An infectious disease crisis becomes a “disaster” when crisis mode decision making by public health officials or institution fails to control the situation, either from an informational or response perspective and substantial social disruption associated with features of community disintegration occurs as a result.

An IDIS category 5 event is the end-point of social strain experienced when cultural protections fail and individuals of a community physically abandon their dwellings or those vital processes necessary for community integration. The concepts of integration and disintegration are not absolute: each community is associated with a given balance of factors that promote integration and disintegration. Disasters tip this balance towards disintegration. This concept therefore encompasses more than simply public health response capacity but a broader social context.

Category 5 infectious disease events are classically observed as the so-called "panic evacuations", which is a misnomer. Observations for years has instead suggested people migrate out of an area of perceived high threat in a manner that attempts to preserve the family unit and other close social ties. It is often observed that these individuals attempt to return to their homes. Thus, an IDIS Category 5 event typically represents transient community disintegration.

Examples of IDIS category 5 events include outbreaks of Ebola hemorrhagic fever in Africa, occasional abrupt appearances of cholera in IDP camps in Africa, and measles in Africa. The 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic induced Category 5 conditions among indigenous peoples in South America. The key is the intersection between the infectious disease event and violation of cultural protections to the point of inducing community disintegration.

In Ningbo, indications of an IDIS Category 5 event were noted with residents within the outbreak zone attempting to flee the area on Day 7, and certainly by Day 30 with the complete destruction of the outbreak zone by fire.

Category 6 - Infectious disease event associated with apocalyptic indicators

The IDIS Category 6 event is typically used to describe historical examples of isolated indigenous peoples confronting an insurmountable infectious disease threat such as measles in an unvaccinated population, smallpox among the American Indians, specific examples during the 1918 influenza pandemic, and Ebola among isolated peoples in the Congo. During such events, the community involved begins to exhibit loss of cohesiveness in the family unit as members of the family become ill and unable to care for each other or decisions are made to abandon other members to protect the larger family unit. More precise indicators of a Category 6 event include observations of otherwise healthy people waiting in their huts, beds, or self-prepared graves to die.

Given that 8 entire families died quickly during the Ningbo plague epidemic in the same community, it is remarkable Category 6 indicators were not reported. It may be hypothesized that swift official engagement that included coordination of the entire community in organized response provided enough perception of situational control to mitigate general feelings of hopelessness. Complete destruction of the outbreak zone by fire on Day 30 was likely perceived to be an expression of control over the situation that definitively ended the epidemic. Category 6 indicators may indeed have appeared, unreported, before Day 30 and most likely around the time of peak fatalities reported on Day 8.

Summary

As shown in Figure 5, the evolution of the plague epidemic in Ningbo followed the progression of an event that quickly elicited a non-routine crisis response by Day 3, followed by significant social disruption by Day 6, social disintegration on Day 7, and ultimately, disaster with the complete destruction of the neighborhood by fire on Day 30. It is possible apocalyptic indicators appeared near the peak of fatalities on Day 8, when it was realized entire families were dying. Subsequent testimonies by survivors suggest they have suffered from symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for years after the event.

---------------

A review of US and British intelligence reporting and analysis of Japanese BW activities in China reveals that US and UK authorities were aware of allegations that Japan was using BW agents against the Chinese populace as early as mid-to-late 1941. Yet intelligence officers and analysts in both countries assessed the intelligence reporting as unreliable or unconfirmed. US intelligence collection until relatively late in the war was sparse. Some intelligence was collected from scientific journals in the 1930s, but most of the more detailed intelligence came from Japanese prisoners of war after 1943. A 1944 US Navy memorandum to the Joint Intelligence Staff detailing all the available reporting on Japan’s BW capabilities and intentions only mentions “unauthenticated” reports of Japanese BW use of plague, including an attack on Changteh. Even a more authoritative War Department assessment of Japan’s BW capabilities and intentions written in mid-1945 claimed that Japan’s BW program was only at an experimental stage with no evidence of mass agent production, and dissemination would be limited to sabotage operations.

From the available record, the Allies focused most of their attention on the Japanese use of plague on the city of Changteh (Chengde) in Hunnan province. Efforts were made to collect intelligence regarding the attack, but the subsequent reporting was viewed with skepticism. Despite Chinese efforts to convince their Western allies of the BW attack on Changteh, British authorities, including their foremost scientific experts, viewed the allegations against the Japanese as unproven. Given that the UK’s Bacteriological Warfare Committee believed that the Changteh case had undergone the greatest scientific scrutiny of all the alleged BW attacks; the other allegations of BW use were deemed less credible.

Allied intelligence had insufficient presence of intelligence assets on the ground in Manchuria to rapidly investigate suspicious signatures of possible biological weapons use. This relates directly to multiple uses of the term “reliable source”, where if a source has not been evaluated by intelligence analysts, then uncertainty related to whether to trust the information impairs further action. It remains debatable whether investment in intelligence assets in Manchuria would have provided 1) more timely information than local media and 2) information considered credible enough to prompt action.

Literature on warning sociology highlights several key points to consider:

It is clear Allied Intelligence considered initial reports to be derived from unreliable sources and therefore, the information was not credible.Upon receipt of warning information, Allied Intelligence was denied access to a key decision point, that of verification because of a lack of pre-positioned trusted ground assets.Even with the presence of pre-positioned assets, it is unclear what how much evidence would have sufficed for action.It is unclear from available evidence what specifically constituted “action” except for verification. It is worth noting the Ningbo epidemic occurred more than a year prior to Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941). It is debatable whether more timely Allied awareness of live field testing of BW agents multiple times would have altered the threat assessment of the Japanese and subsequent defense posture at Pearl Harbor.

Implications For Detection and Early Warning in Today’s Society

If the same epidemic of plague were to occur today in Ningbo, it would not have had the same impact owing to effective rodent control, modern sanitation, and access to modern antibiotics and healthcare. There is little doubt the discovery of a human plague outbreak in any modern city generates IDIS Category 3 (non-routine crisis) conditions. The mere mention of plague in today’s society tends to prompt immediate media attention, which varies somewhat across societies. If considered in less developed areas of the world, plague epidemics are increasingly less likely to pass unnoticed in today’s rapidly expanding internet.

However, human recognition of unusual, non-routine health events involving plague is required in order to contemplate closer scrutiny. This raises the question of thresholds for action, a process that is generally intolerant of false alarms. Hesitation in the verification process virtually ensures loss of rapidly time-decaying evidence.

There have been assertions that pre-event indicators of BW releases are impossible to obtain. This is an inaccuracy. Detection of research and development in a laboratory may be difficult to nearly impossible. Field-testing is difficult to detect but not impossible. The index of suspicion should remain high in the face of local assertion of a grossly unusual infectious disease event, and mechanisms to support rapid decision-making and verification tolerant of high false positive rates should be contemplated.

source:

Operational Biosurveillance

The practice of operational biosurveillance.

http://biosurveillance.typepad.com/biosurveillance/2013/05/echoes-of-the-past-deliberate-release-of-plague-in-ningpo-manchuria.html

reprinted for information only and without any responsibility for the exact content of the information above.

If you have different information please comment on it and mention your source